I got many good responses to my Considerations On Cost Disease post, both in the comments and elsewhere. A lot of people thought the explanation was obvious; unfortunately, they all disagreed on what the obvious explanation was. Below are some of the responses I found most interesting.

So, what is really happening? I think Scott nearly gets there. Things cost 10 times as much, 10 times more than they used to and 10 times more than in other countries. It’s not going to wages. It’s not going to profits. So where is it going?

The unavoidable answer: The number of people it takes to produce these goods is skyrocketing. Labor productivity — number of people per quality adjusted output — declined by a factor of 10 in these areas. It pretty much has to be that: if the money is not going to profits, to to each employee, it must be going to the number of employees.

How can that happen? Our machines are better than ever, as Scott points out. Well, we (and especially we economists) pay too much attention to snazzy gadgets. Productivity depends on organizations not just on gadgets. Southwest figured out how to turn an airplane around in 20 minutes, and it still takes United an hour.

Contrariwise, I think we know where the extra people are. The ratio of teachers to students hasn’t gone down a lot — but the ratio of administrators to students has shot up. Most large public school systems spend more than half their budget on administrators. Similarly, class sizes at most colleges and universities haven’t changed that much — but administrative staff have exploded. There are 2.5 people handling insurance claims for every doctor. Construction sites have always had a lot of people standing around for every one actually working the machine. But now for every person operating the machine there is an army of planners, regulators, lawyers, administrative staff, consultants and so on. (I welcome pointers to good graphs and numbers on this sort of thing.)

So, my bottom line: administrative bloat.

Well, how does bloat come about? Regulations and law are, as Scott mentions, part of the problem. These are all areas either run by the government or with large government involvement. But the real key is, I think lack of competition. These are above all areas with not much competition. In turn, however, they are not by a long shot “natural monopolies” or failure of some free market. The main effect of our regulatory and legal system is not so much to directly raise costs, as it is to lessen competition (that is often its purpose). The lack of competition leads to the cost disease.

Though textbooks teach that monopoly leads to profits, it doesn’t “The best of all monopoly profits is a quiet life” said Hicks. Everywhere we see businesses protected from competition, especially highly regulated businesses, we see the cost disease spreading. And it spreads largely by forcing companies to hire loads of useless people.

Yes, technical regress can happen. Productivity depends as much on the functioning of large organizations, and the overall legal and regulatory system in which they operate, as it does on gadgets. We can indeed “forget” how those work. Like our ancestors peer at the buildings, aqueducts, dams, roads, and bridges put up by our ancestors, whether Roman or American, and wonder just how they did it.

I think there is another dynamic that’s being ignored — and I would be surprised if an economist ignored it, but I’ll blame Scott’s eclectic ad-hoc education for why he doesn’t discuss the elephant in the room — Superior goods.

For those who don’t remember their Economics classes, imagine a guy who makes $40,000/year and eats chicken for dinner 3 nights a week. He gets a huge 50% raise, to $60,000/year, and suddenly has extra money to spend — his disposable income probably tripled or quadrupled. Before the hedonic treadmill kicks in, and he decides to waste all the money on higher rent and nicer cars, he changes his diet. But he won’t start eating chicken 10 times a week — he’ll start eating steak. When people get more money, they replace cheap “inferior” goods with expensive “superior” goods. And steak is a superior good.

But how many times a week will people eat steak? Two? Five? Americans as a whole got really rich in the 1940s and 1950s, and needed someplace to start spending their newfound wealth. What do people spend extra money on? Entertainment is now pretty cheap, and there are only so many nights a week you see a movie, and only so many $20/month MMORPGs you’re going to pay for. You aren’t going to pay 5 times as much for a slightly better video game or movie — and although you might pay double for 3D-Imax, there’s not much room for growth in that 5%.

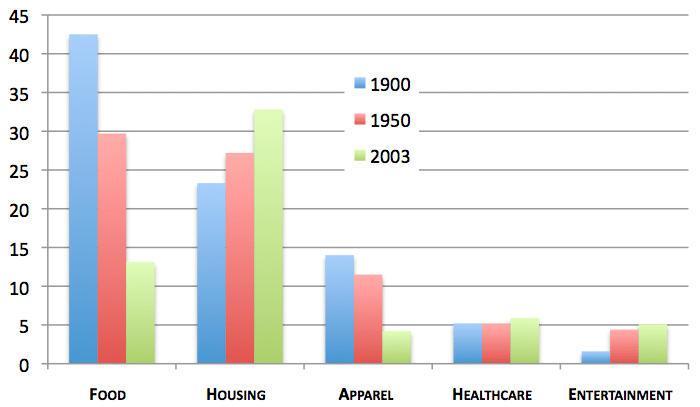

The Atlantic had a piece on this several years ago, with the following chart:

Food, including rising steak consumption, decreased to a negligible part of people’s budgets, as housing started rising.In this chart, the reason healthcare hasn’t really shot up to the extent Scott discussed, as the article notes, is because most of the cost is via pre-tax employer spending. The other big change the article discusses is that after 1950 or so, everyone got cars, and commuted from their more expensive suburban houses — which is effectively an implicit increase in housing cost.

And at some point, bigger houses and nicer cars begin to saturate; a Tesla is nicer than my Hyundai, and I’d love one, but not enough to upgrade for 3x the cost. I know how much better a Tesla is — I’ve seen them.

Limitless Demand, Invisible SupplyThere are only a few things that we have a limitless demand for, but very limited ability to judge the impact of our spending. What are they?

I think this is one big missing piece of the puzzle; in both healthcare and education, we want improvements, and they are worth a ton, but we can’t figure out how much the marginal spending improves things. So we pour money into these sectors.

Scott thinks this means that teachers’ and doctors’ wages should rise, but they don’t. I think it’s obvious why; they supply isn’t very limited. And the marginal impact of two teachers versus one, or a team of doctors versus one, isn’t huge. (Class size matters, but we have tons of teachers — with no shortage in sight, there is no price pressure.)

What sucks up the increased money? Dollars, both public and private, chasing hard to find benefits.

I’d spend money to improve my health, both mental and physical, but how? Extra medical diagnostics to catch problems, pricier but marginally more effective drugs, chiropractors, probably useless supplements — all are exploding in popularity. How much do they improve health? I don’t really know — not much, but I’d probably try something if it might be useful.

I’m spending a ton of money on preschool for my kids. Why? Because it helps, according to the studies. How much better is the $15,000/year daycare versus the $8,000 a year program a friend of mine runs in her house? Unclear, but I’m certainly not the only one spending big bucks. Why spend less, if education is the most superior good around?

How much better is Harvard than a subsidized in-state school, or four years of that school versus 2 years of cheap community college before transferring in? The studies seem to suggest that most of the benefit is really because the kids who get into the better schools. And Scott knows that this is happening.

We pour money into schools and medicine in order to improve things, but where does the money go? Into efforts to improve things, of course. But I’ve argued at length before that bureaucracy is bad at incentivizing things, especially when goals are unclear. So the money goes to sinkholes like more bureaucrats and clever manipulation of the metrics that are used to allocate the money.

As long as we’re incentivized to improve things that we’re unsure how to improve, the incentives to pour money into them unwisely will continue, and costs will rise. That’s not the entire answer, but it’s a central dynamic that leads to many of the things Scott is talking about — so hopefully that reduces Scott’s fears a bit.

A reader who wishes to remain anonymous emails me, saying:

In the business I know – hedge funds – I am aware of tiny operators running perfectly functional one-person shops on a shoestring, who take advantage of workarounds for legal and regulatory costs (like http://www.riainabox.com/. Then there are folks like me who are trying to “be legit” and hope to attract the big money from pensions and big banks. Those folks’ decisions are all made across major principal/agent divides where agents are incentivized not to take risks. So, they force hedge funds into an arms race of insanely paranoid “best practices” to compete for their money. So… my set up costs (which so far seem to have been too little rather than too much) were more than 10x what they could have been.

I guess this supports the “institutional risk tolerance” angle. There must be similar massive unseen frictions probably in many industries that go into “checking boxes”.

Relatedly, a pet theory of mine is that “organizational complexity” imposes enormous and not fully appreciated costs, which probably grow quadratically with organization size. I’d predict, without Googling, that the the US military, just as a function of being so large, has >75% of its personal doing effectively administrative/logistical things, and that you could probably find funny examples of organizational-overhead-proliferation like an HR department so big it needed its own (meta-)HR department.

That could be one force behind rising costs; it definitely seems important for K-12 education. But it doesn’t explain why the U.S. is so much worse than countries such as France, Germany or Japan. Those countries are about as productive as the U.S., so their cost disease should be comparable. Something else must be afoot.

Another usual suspect is government intervention. The government subsidizes college through cheap loans, purchases infrastructure, restricts housing supply, and intervenes heavily in the health-care market. It’s probably part of the problem in these areas, especially in urban housing markets.

But again, government intervention struggles to explain the difference between the U.S. and other rich nations. In most countries, health care is mainly paid for by the government — many countries have nationalized the industry outright. Yet their health outcomes are broadly similar to those in the U.S., or even a little bit better. Other countries have strong unions and high land acquisition costs — often stronger and higher than the U.S. — but their infrastructure is much cheaper. And there is no law or regulation propping up high wealth-management fees or real-estate commissions. In general, lower-cost places like Japan and Europe have more regulation and more interventionism than the U.S.

So if cost disease and government can at most be only part of the story, what’s going on? One possibility Alexander raises is that “markets might just not work.” In other words, there might be large market failures going on.

The health-care market naturally has a lot of adverse selection — people with poor health are more inclined to buy insurance. That means insurance companies, knowing its customers tend to be those with poorer health, charge higher prices. Also, hospitals could be local monopolies. And college education could be costly in part because of asymmetric information — if Americans tend to vary more than people in other countries with respect to work ethnic and natural ability, they might have to spend more on college to prove themselves. This is known as signaling.

When high costs are due to market failures, interventionist government can be the solution instead of the problem — provided the intervention is done right. So the more active governments of countries like Europe and Japan might be successfully holding down costs that would otherwise balloon to inefficient levels.

But there’s one more possibility — one that gets taught in few economics classes. There is almost certainly some level of pure trickery in the economy — people paying more than they should, because they don’t have the time or knowledge to look for better prices, or because they trust people they shouldn’t trust.

This is the thesis of the book “Phishing for Phools,” by Nobel-winning economists George Akerlof and Robert Shiller. The authors advance the disturbing thesis that sellers will continually look for ways to dupe customers into paying more than they should, and that these efforts will always be partially successful. In Akerlof and Shiller’s reckoning, markets don’t just sometimes fail — they are inherently subject to both deceit and mistakes.

That could explain a number of unsettling empirical results in the economics literature. For example, transparency reduces prices substantially in health-care equipment markets. More complex and opaque mortgage-backed securities failed at higher rates in the financial crisis. In these and other cases, buyers paid too much because they didn’t know what they were buying. Whether that’s due to trickery, or to the difficulty of gathering accurate information, it’s not good — in an efficient economy, everyone will know what they’re buying.

So it’s possible that many of those anomalously high U.S. costs are due to the natural informational problems of markets.

It’s pretty easy to tell a libertarian story where markets work fine, but government intrusions into these markets have rendered them so unfree that they no longer function the way they’re supposed to. And I think that is at least part of the story here. Yes, these things are often procured from private parties. But everywhere you look you see the government: blocking new entry (through accreditation standards, “certificate of need” laws, and zoning and building codes), while simultaneously subsidizing the purchases through artificially cheap loans and often, direct price subsidies. It would be sort of shocking if restricted supply combined with stimulated demand didn’t produce rapidly rising prices. Meanwhile, in areas that the government largely leaves alone (such as Lasik), we pretty much see what you’d expect: falling prices and improving consumer service.

But that’s perhaps a little simplistic. Agriculture is also the focus of a great deal of government intervention, as are sundry things such as air travel, and we don’t see the same phenomenon there. So we need to dig a little deeper and describe what’s special about these three sectors (we’ll leave public transportation out of it, because there, the answer is pretty much “union featherbedding combined with increasingly dysfunctional procurement and regulatory processes”).

First, and most obviously, they involve vital purchases made on long time horizons, and with considerable uncertainty. Food is more vital than health care to our well-being, but its price and quality are really easy to assess: if you buy a piece of fruit, you know pretty quickly whether you liked it or not. This is a robust market, and it’s going to take communist-level intervention to fundamentally mess it up so that food is both scarce and not very good.

Homes, schooling and health care, on the other hand, are more complicated products. You don’t know when you buy them how much value they will be to you, and it is often difficult for a lay person to assess the quality of the product. You can read hospital rankings and pay a home inspector, but these things only go so far.

The fact that these are expensive purchases that can go terribly wrong creates a great deal of pressure for the government to intervene. As ours has, over and over, in all sorts of ways.

And at the risk of giving up a little bit of my libertarian cred, I’ll say that government intervention in these markets did not have to be as expensive-making as it has turned out to be in America. Other countries have these sorts of problems too, but they’re nowhere near as large as ours.

Part of that is just that we’re richer than most of those other countries. We were going to spend the portion of our budgets no longer needed for food somewhere, and health care, education and housing are pretty good candidates. But that’s only part of the story. A big part of the story is that America just isn’t very good at regulation. When you talk to people who live elsewhere about what their government does, one thing that really strikes you about those conversations is how much more competent other rich industrial governments seem to be at regulating things and delivering services. Their bureaucracies are not perfect, but they are better than ours.

That’s not to say that America could have an awesome big government. Our regulatory state has been incompetent compared to others for decades, since long before the Reagan Revolution that Democrats like to blame. There are many, many factors in this, from our immigration history (vital to understanding how modern urban bureaucracies work in this country), to the fact that we have many competing centers of power instead of a single unified government providing over a single bureaucratic hierarchy. There is no way to fix this on a national level, and even at the level of local bureaucratic reform, it’s darned near impossible.

In other words, this is probably what we’re stuck with. It may not be Baumol’s cost disease — but it’s potentially even more serious, and it’s going to be a lingering condition.

I certainly don’t claim to have all the answers, but I do feel that much of the problem reflects the fact that governments often cover the cost of services in those three areas. This leads producers to spend more than the socially optimal amount on these products. I’m going to provide some examples, but before doing so recall that economic theory predicts that costs in those areas should be wildly excessive. If the government paid 90% of the cost of any car you bought, and that didn’t lead to lots more people buying Porsches and Ferraris, then we’d have a major puzzle on our hands.

Scott mentions that private for-profit hospitals are also quite expensive. But even there, costs are largely paid for by the government. Close to half of all health care spending is directly paid for by the government (Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans, government employees, etc.) and a large share of the rest is indirectly paid for by taxpayers because health insurance is not just income tax free, but also payroll tax free. I’d be stunned if health care spending had not soared in recent decades.

A sizable share of my health care spending has been unneeded, and I’m fairly healthy. I met one person in their 80s who had a normal cold and went to see the doctor. They said it was probably just a normal cold, but let’s put you in the hospital overnight and do some tests, just in case. There was nothing wrong, and the bill the next day was something in the $5000 to $10,000 range, I forget the exact amount. This must happen all the time. No way would they have opted for those services if Medicare weren’t picking up the tab.

Just to be clear, I don’t think any monocausal explanation is enough. Governments also pay for health care in other countries, and the costs are far lower. It’s likely the interaction of the US government picking up much of the tab, plus insurance regulations, plus American-style litigation, plus powerful provider lobbies that prevent European-style cost controls, etc., etc., lead to our unusually high cost structure. So don’t take this as a screed against “socialized medicine.” I’m making a narrower point, that a country where the government picks up most of the costs, and doesn’t have effective regulations to hold down spending, is likely to end up with very expensive medicine.

To be fair, there is evidence from veterinary medicine that demand for pet care has also soared, and that suggests people are becoming more risk averse, even for their pets. But there is also evidence cutting the other way. Plastic surgery has not seen costs skyrocket. (Both are medical fields where people tend to pay out of pocket.)

I started working at Bentley in 1982, teaching 4 courses a semester. When I retired in 2015, I was making 7 times as much in nominal terms (nearly 3 times as much in real terms), and I was teaching 2 courses per semester. Thus I was being paid 14 times more per class (nearly 6 times as much in real terms). No wonder higher education costs have soared! (Even salaries for new hires have risen sharply in real terms.) Interestingly, the size of the student body at Bentley didn’t change noticeably over that period (about 4000 undergrads.) But the physical size of the school rose dramatically, with many new buildings full of much fancier equipment. Right now they are building a new hockey arena. There are more non-teaching employees. You can debate whether living standards for Americans have risen over time, but there’s no doubt that living standards for Americans age 18-22 have risen over time—by a lot.

As far as elementary school, my daughter had 2, 3, and once even 4 teachers in her classroom, with about 18 students. We had one teacher for 30 students when I was young. (I’m told classes are even bigger in Japan, and they don’t have janitors in their schools. The students must mop the floors. I love Japan!)

There are also lots more rules and regulations. By the end of my career, I felt almost like I was spending as much time teaching 2 classes as I used to spend teaching 4. Many of these rules were well intentioned, but in the end I really don’t think they led to students learning any more than back in 1982. I wonder if Dodd/Frank is now making small town banking a frustrating profession in the way that earlier regs made medicine and teaching increasing frustrating professions.

People say this is a disease of the service sector. But I don’t see skyrocketing prices in restaurants, dry clearers, barbers and lots of other service industries where people pay out of pocket.

The same is true of construction. Scott estimates that NYC subways cost 20 times as much as in 1900, even adjusting for inflation. The real cost of other types of construction (such as new homes), has risen far less. Again, people pay for homes out of pocket, but government pays for subways. Do I even need to mention the cost of weapons system like the F-35?

To summarize, the case of pet medicine shows that costs can rise rapidly even when people pay out of pocket. But the biggest and most important examples of cost inflation are in precisely those industries where government picks up a major part of the tab–health, education, and government procurement of complex products. And excessive cost inflation is exactly what economic theory predicts will happen when governments heavily subsidize an activity, without adequate cost regulations. Just as excessive risk taking is exactly what economic theory predicts will happen if government insures bank deposits, without adequate risk regulations. Let’s not be surprised if the things that happen, are exactly what the textbooks predict would happen. Even FDR predicted that deposit insurance would lead to reckless behavior by banks, and he (reluctantly) signed the bill into law.

I’ve seen some evidence that corporations can be equally vulnerable to cost disease as public institutions.

For example, since the 1980s CEO pay has quintupled despite the lack of any growth in profits or otherwise to justify this. Now this is probably going to result in far smaller effects on overall cost, but it still stands as a demonstration of how market failure can occur and result in large cost increases in these firms.

I would venture that many firms have seen huge increases in both revenues and costs so that when you adjust profit for inflation it hasn’t really changed at all, on average.

What you observe is fifty years of optimization of wealth extraction. Price outcomes depend on the contributions of hundreds of participants. Every participant optimizes his/her earnings, exerting a constant upward pressure on price. Participants become ever more expert at getting rich. Wealth-extraction schemes (scams) are refined and optimized (in all markets), and price increases are pushed downstream (in markets where buyers can’t push back). Radical price increases reflect markets where consumers have reduced ability to push back:

– complex markets (can’t understand)

– opaque markets (can’t see)

– entrenched/highly-regulated markets (can’t modify)

– necessary-to-keep-living markets (can’t avoid)

– limited-quantity markets (really want)

– intermediated markets where the end buyer doesn’t decide how things are purchased (don’t choose)Some systems are resistant to contributors’ efforts to extract wealth and some systems are not. There’s an equilibrium between cost and readiness to pay. To reduce the costs in expensive domains, willingness to pay the high costs has to be reduced. As long as the buyer won’t or can’t say no, costs will increase through the entire production process. There won’t necessarily be one big obvious rip-off, but every participant will optimize the heck out of his contribution and the overall pressure will push costs up.

Could one provide a cheaper alternative in these domains? Sure for a little while, but if the bottom line is that people are willing to pay more for the service the prices will creep back up.

The only exception would be where the new, lower-priced, alternative sets a new standard and buyers refuse to continue paying the old prices. See https://stratechery.com/2016/dollar-shave-club-and-the-disruption-of-everything/ for a great article about this.

My favorite example of ridiculous order-of-magnitude type cost increases is nuclear power plant construction costs. The plots from this paper illustrate it nicely.

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/292964046_fig6_Overnight-Construction-Cost-and-Construction-Duration-of-US-Nuclear-Reactors-ColorExcept, in the case of power plant costs, the causes – at least, for the increasing US costs – are quite a bit more apparent. Pre TMI, US costs were in line with the rest of the world’s cost. Post TMI, not so much. New regulatory burdens all by themselves increased the cost of new plants by a factor of ten. Now, this is of course not proof that any of the other problems that Scott mentioned are entirely – or even mostly – caused by increasing regulatory burdens. It does however, show that government institutions as awful as the NRC do exist, and that their effects can raise costs by the amounts seen health care, education, etc…”

[Fear of lawsuits] is well understood as the cause of the substantial rise in light airplane prices since 1970. A single-engine, four-seat Cessna 172 cost an inflation-adjusted $77,000 in 1970. A substantially identical airplane cost $163,000 in 1986. And went out of production the next year, because people weren’t willing to pay that price. When congress passed laws relaxing the manufacturer’s liability for older airplanes, Cessna was able to reinstate production in 1996 at an inflation-adjusted $190,000. Today, the price seems to literally be “if you have to ask, you can’t afford it”; the manufacturer only advertises fleet sales, but I’d estimate about $400,000 (of which ~$100K is fancy electronics that didn’t exist in 1986 and weren’t standard in 1996).

In this case it is particularly easy to pull out the lawsuit/liability effect because there aren’t many cofounders. The 1986 Cessna is so little changed from the 1970 model that they sell at about the same price on the used market when controlled for condition and total flight time. And fear of lawsuits didn’t manifest as safety enhancements of inscrutable cost and value, because light airplane crashes are almost always due to Stupid Pilot Tricks and almost everything that a manufacturer could do to mitigate that (e.g. tricycle landing gear) was standard in 1970. But the manufacturers still get sued, and have to pay millions, so there’s nothing to be done but pay for liability insurance. And, second-order effect, cut production when your customers start balking at the increased prices, so you have to amortize the fixed costs of actually building airplanes over a smaller sales volume.

So, a doubling in price over fifteen or so years, a quadrupling over fifty years in spite of Congress noticing the problem and trying to mitigate it, attributable to safety/liability concerns but not resulting in actual safety improvements. I have no trouble believing something similar is happening in other industries but is harder to discern because too many other things are happening at the same time.

Wikipedia suggests that almost all of those other countries have litigation rules that make weak civil cases more costly, which seems like evidence in favor of the litigation hypothesis. It also means that there’s a relatively straightforward solution.

Doug on Marginal Revolution, in response to a lot of people asking whether maybe we were just calculating the CPI wrong:

That’s a plausible hypothesis, but viewed through that frame of reference, median wages have also gone down tremendously. It’s still the case that the median person spends at least six times more of their paycheck on healthcare. If healthcare is a closer metric to “true prices” then manufactured good, then that means median wages have fallen by around 80%. It also means that overall GDP has crashed since 1970, since the price deflator now averages 6-7%, and nominal GDP has only averaged around 4%. It would mean that the economy has literally been in recession 90% of the past 40 years.

The only reason we’re not all starving in the street is from the miraculous gains in manufacturing productivity and automation. But again, in this framework, that process is largely exogenous to the terrible macroeconomic situation. If those gains slow down even a little, and the macro trends continue, we’re probably facing imminent economic collapse. So maybe this is a plausible hypothesis, but it certainly comes with a whole lot of extreme implications. I think medicine/education specific cost disease is a much more likely explanation.

One commonality in the examples cited is disintermediation/subsidies. College is paid for by a third party, and financed by generous government loans. Generous in the sense that they are easy to get, not easy to get out of. Health care has massive tax subsidies, and for a good period of time felt “free” to employees. Public schooling is paid for indirectly.

Regarding the section on risk aversion, I happen to be in the playground business. The most common injury is broken bones from a fall. Consequently, our industry has ended up with poured in place surfacing, which costs 10x as much as mulch or pea gravel. It is wonderful stuff, but really increases the cost of the playground. Again, no one pays directly for their playground, and the paying party cannot risk not being in tune with the regulations.

Markets cannot function if the risk reward relationship is not direct.

In all of these problem sectors it seems the resources consumed in each industry has shifted to servicing and extending the definition of the marginal ‘customer’. This can explain I think some of the above

E.g.. 40 years ago hospitals received 100 customers. Ranked, patients 1-20 died. And no one really tried to save them (some comfort but that was it). Today they are trying (are obliged) to try to save patients no 5-15 (the 85 year old with triple bypass, 20 week premie). The total no of staff needed for this task swamps increases in individual productivity. You just need more people, even if they each are more productive or trained than in the pasts. So salaries for each does not go up that much, there are just more of them, total cost go up, and outcomes over the patients treated are somewhat but not much better (some now make it but some fraction still die). Hence medical curve shows some improvement but not 1:1 with cost.

In education, in the 1950-1970s we could afford to socially promote non-academically inclined students, not really expend effort on them as long as they kept quiet in class, then have them leave at age 16 to go work at Ford. Universities could count on getting the higher performing students. Today, we have to deliver much weaker students all the way to the end of high school, also force many into college. And ALL the extra resources go to get this new lower end close to what used to be the minimal university student performance. The top cohort gets little extra resources and has not really improved. Hence, the scores across the new ‘extended’ student population stays flat.

I base this partly on what I have seen from my wife (engineering professor at top university), resources are heavily consumed by the lower performing students, top students have better opportunities than 20 years ago but in general the resources are much less focused on them than on the marginal students.

So if you assume these industries for whatever reason shifted focus to servicing deeper into the tail of the population aptitude/effort over the years (I am not saying this is good/bad, was for social reasons, for humanistic reasons or making any comment), this would very much explain the overall cost rise, coupled with the lack of desired improvement in statistics measured across the population that now gets services as a whole.

In short, in the US we define policies that drive costs based on the tail of the population, but we experience performance on the average. As an immigrant from a third world country I think this is a big difference often invisible to the US-born citizens I talk to. Maybe why this is a great country and I am here. All I can say is that it is a world view that is not common world wide. Where I grew up, No Child Left Behind law would have been designed as 1 Child Left Behind. There just were not the resources, but more important, it was just more socially acceptable to just halve the no of slots halfway through an academic program, for example.

So I guess the question is why are we so focused on pushing services into the tails and will we continue to do so? Does society really benefit from having a larger fraction of the population capable of doing crappy algebra? Clearly there will be some point where the cost becomes prohibitive and it will stop: maybe that is what we are seeing now. But it is stunning that this was a 50 year process — if the dynamics in social policy “markets” are that slow it is going to be really difficult to manage.

I can’t help but wonder if part of the ever-expanding expenses isn’t that we mediate our interactions through the legal system more than we used to.

What got me thinking about it was what I’m working on this week. To answer Incurian’s question above about why I was posting during the workday, I was avoiding working on a report for selecting a contractor for a project I’m working on. (I owe the taxpayer about three hours this weekend, since I spent time on Friday here and reading about the Oroville Dam spillway.)

We had contractors submit proposals, and we had two structural engineers and a construction quality assurance rep sit in a room for three days, writing our individual reports about each proposal, then coming to agreement about how we rate them. Then I have to write a report summarizing all of our individual reports, which gets fed into the arcane machine that will eventually spit out an award. This process costs about $10,000, and had zero value for evaluating the proposals. However, it has to be done this way or we’ll get dragged around in court by an offeror’s lawyer if they choose to make a case of their rejection. I think that in years past they’d use a simple low-bid process, which has its own problems, or the rejected contractors would bitch to their Congressmen or something but wouldn’t literally make a federal case of it.

I think you gave short shrift to libertarian explanations of this phenomena. In particular, the Kling Theory of Public Choice may explain a significant fraction of cost disease: public policy will always choose to subsidize demand and restrict supply. If you restrict supply holding everything else equal, prices will go up. If you subsidize demand holding everything else equal, prices will go up. If you do both, prices will really go up.

(1) Healthcare: The government restricts the supply of all healthcare professionals (for example, doctors, nurses, CNAs, pharmacists, dentists, LPNs, etc.) via occupational licensing. (I should note that maybe everyone can get behind the simple idea that the number of doctors per 10,000 people in the US should at least remain constant over time and not go down, as it has.) It restricts the supply of healthcare organizations (for example, hospitals, surgery centers, etc.) via onerous regulations, like the very ridiculous “certificate-of-need“. You have already explained in previous posts how things like the FDA restrict the supply of generic drugs. In terms of demand, the government subsidizes health insurance via the corporate income tax code, CHIP, the Obamacare marketplace, Medicaid, Medicare, etc.

(2) Education: I have done less investigation into this sector’s regulations. You mentioned Title IX. David Friedman has some nice blog posts on how the American Bar Association’s regulations on law schools make cheap law schools impossible. (This same concept also applies to healthcare-related professional schools, by the way.) If Bryan Caplan is right about signaling, a lot of education involves negative externalities, so it should be taxed or limited by the government. Instead, it subsidizes demand via loans. K-12 education, meanwhile, receives massive subsidies from the government; everyone can enjoy a totally free K-12 education.

(3) Real estate: Land-use regulations restrict the supply of housing. (Explanations of this can be found by googling “Matt Yglesias housing”.) It also subsidizes housing via Section 8, various other HUD programs, Freddie Mac, the mortgage-interest tax deduction, etc.

In short, any industry that the United States government has a heavy hand in has/will experience cost disease.

Scott, help me out here because I’ve read a long article about the mysterious nature of rising costs in certain sectors as well as hundreds of bemused comments, and the article had no more than a throwaway paragraph saying that maybe rising inequality is a sign that the ‘missing’ money is ending up in the pockets of the super-wealthy elite.

I come from a left-wing perspective, so I hope you can see that to me ex nihilo, “the super wealthy are becoming much richer than was historically the case, also all of these important services are becoming way more expensive than they used to be, but the one does not explain the other” looks like an extraordinary claim. I would like to see more evidence presented that this is not the case before updating in this direction!

In particular, I can see that a large majority of the odd features you have picked out about these services are acting exactly as predicted in Das Kapital volume 2, where Marx studies the process of realisation of invested capital (ie, money spent on labour, materials, tools etc) as the principal plus surplus value in money form. In particular, some of his predictions were:

1. Gains made by workers through collective action in sites of production can be taken away again by the landlord, the grocer, the financier etc.

2. The difficulty in the realisation of capital will incentivise businesses to strive for monopoly positions (whether by government mandate, mutual cooperations, quasi-monopolies such as real estate, branding and advertising).

3. The tensions between the production of surplus value and the realisation of surplus value will tend to set certain sectors of capital against one another – for example landlords would prefer if workers were well paid, but had to spend larger amounts of money on rent whereas factory owners would prefer to pay workers as little as possible, and that includes low housing costs.

Later analysis in the tradition of Marx have noticed that financial capital these days is doing very very well compared to workers, but also compared to traditional industrialists. And four out of the five of your examples are fields in which debt and financing plays a very large role. It’s pretty easy to see that financial capital would be incentivised to make these things more expensive so that they can extract more money through larger loans and financing. (I’m not certain about subways. Are they typically debt-financed?).

Financial capital certainly has the economic and political power to push for this, and they don’t particularly care if they squeeze other holders of capital along they way. They are debt-financed fields in which large monopoly powers exist for one reason or another. And while I acknowledge that bureacratic bloat is certainly playing its role, I’m baffled by the relative lack of consideration of normal capitalist tendencies on this thread. As far as I can see it is the single most important factor driving up the costs of these services. Please present me with evidence that I am wrong about this!

Some additional links less-directly related or less easy to excerpt:

National Center for Policy Analysis: Should All Medicine Work Like Cosmetic Surgery? Because plastic surgery isn’t a life-or-death need, it’s not covered by insurance. Costs in the sector have risen 30% since 1992, compared to 118% for other types of health care. Does this mean that being sheltered from the insurance system has sheltered it from cost disease?

The American Interest: Why Can’t We Have Nice Things? A breakdown of exactly why infrastructure and transportation projects cost so much more in the US than elsewhere, with an eye for Trump’s promise of $1 trillion extra infrastructure spending.

Arnold Kling: What I Believe About Education. I have to include one “it’s all the teachers’ unions fault” post for completeness here.

Neerav Kingsland on education spending and the role of charter schools

The comment thread on Marginal Revolution contains some insight

The Incidental Economist: What Makes The US Health Care System So Expensive FAQ. From July 2011. Includes links to a lot of other things.

And some additional comments of my own:

I think any explanation that starts with “well, we have so much money now that we have to spend it on something…” ignores that many people do not have so much money, and in fact are really poor, but they get the same education and health care as the rest of us. If the problem were just “rich people looking for places to throw their money away”, there would be other options for poor people who don’t want to do that, the same way rich people have fancy restaurants where they can throw their money away and poor people have McDonalds.

Any explanation of the form “evil capitalists are scamming the rest of us for profit” has to explain why the cost increases are in the industries least exposed to evil capitalists. K-12 education is entirely nonprofit. Colleges are a mix but generally not owned by a single rich guy who gets all the money. My hospital is owned by an order of nuns; studies show that government hospitals have higher costs than for-profit ones. Meanwhile, the industries with the actual evil capitalists – tech, retail, restaurants, natural resources – seem mostly immune to the cost disease. This is not promising. Also, this wouldn’t explain why so much of the money seems to be going to administrators/bells-and-whistles. If prices increase by $100,000, and the money goes to hiring two extra $50,000/year administrators, how does this help the capitalist profiting off it all?

Any explanation of the form “administrative bloat” or “inefficiency” has to explain why non-bloated alternatives don’t pop up or become popular. I’m sure the CEO of Ford would love to just stop doing his job and approve every single funding request that passes his desk and pay for it by jacking up the price of cars, but at some point if he did that too much we’d all just buy Toyotas instead. Although there are some barriers to competition in the hospital market, there are fewer such barriers in the college, private school, and ambulatory clinic market. Why hasn’t competition discouraged administrative bloat here the same way it does in other industries?

Maybe a good time to reread the post How Likely Are Multifactorial Trends?

I do tend to think that if we regard people’s comments in the linked sources as votes, and adjust for known info (E.g. CEO pay *is mostly* justified [Google CEO pay Adam Smith Institute for references], and as Scott Sumner points out (pace Noah Smith), the US does not have effective ways of controlling healthcare costs as a result of its hybrid system. Who pays doesn’t tell us enough about how a market works. Also we need to know in which ways they pay, and what the payees are allowed to do) the most plausible explanation is some combination of government mis/overregulation (Perverse incentives+decreased competition) plus some peculiarities of the markets involved (Which interact with the previous reason). I would say it is 70-20-10 government/markets/status goods, but I admit I haven’t done my own research on this, so this is more of a statement of priors modified by the opinions of the above respondents.

I am sorry if this comes across as snarky but it really has to be said. “CEO pay is mostly justified” is not “A known fact”. It is a deeply contested claim debated by mounds of papers and very skilled and learned academics. A passing reference to work by the Adam Smith institute is in no way sufficient to make it a given for purposes of discussion. On a personal level having done a fair bit of reading on the subject I am very confident that CEO salaries are inflated by various forms of institution all capture and cultural malaise, but I would never expect that this certainly be treated as a “known fact” for the purposes of discussion.

I thus reduce my confidence in that claim and I will have to look into the literature myself. References would be appreciated.

Will post some tomorrow

Does it really matter though? Even if executive compensation is totally bonkers, it’s such a small component of the overall costs as to be negligible. And it still doesn’t explain why costs are particularly out of control in e.g. health and education (not where the most bonkers executive pay happens).

Consider the Oracle corporation. Per their filings they paid their top executives a bit less than $200 million in fiscal 2016. But that was on $37 billion in revenue – so top executive pay is just a bit more than half a percent of that. Tiny.

Or in health care, it’s common to blame “greedy profit-obsessed insurance companies”. But say you cut out every dime of the profit – congratulations, you’ve cut total costs by maybe 5-10%. Not nothing, but hardly sufficient to explain the dectupled costs (and it’s not like insurance companies used to be non-profit). Something else is going on.

Is half a percent of revenue tiny? What percent of profits is it? What percent of their total wages across all tiers of employees? Why should it be considered as a percentage of revenue, other than that being the largest number you can name to compare it to?

Well, they currently have 136,236 employees, which means that they could take all of that executive pay and split it to provide their workers with an extra

1467.74986607

dollars each

keeping in mind of course that you still have to pay executives something and it’s usually higher than the average worker, you could probably shave that down to 1,000 extra

which is nice, don’t get me wrong. but is it a make-or-break figure? And keep in mind that these guys do seem to be overpaid moreso than other CEOs, which is probably why he brought them up as an example.

Couple other things to note – most of the compensation for Oracle executives (and this seems true at most companies) is in the form of equity rather than straight salary. I don’t know exactly what restrictions they may have on the equity they receive.

Another thought though – how much of increased CEO pay is due to increased maximum company size, due to globalization and mergers? WARNING: major simplification ahead. As noted, Oracle’s total employment is >100k. So break them up into 10 smaller companies, each with a CEO getting $4 million instead of $40 million, and suddenly CEO pay relative to the average worker looks more sane even though total executive compensation stays the same.

And I wonder how much of American income inequality is driven by the massive size of our largest companies – we’re home to a lot of global company CEOs making up our top 0.1%. Move them all to Denmark and suddenly their inequality shoots through the roof while ours drops, but the life of Joe Schmoe and Josef Schmosen doesn’t change noticeably.

Seriously, anyone complaining about CEO pay as a source of “rising costs” or “decreased employee pay” or “reduced shareholder return” has loudly announced that they don’t understand anything. It’s insignificant.

And I think CEOs are overpaid.

I suppose I should comment here:

-When I pointed out the rise in executive pay, it was not trying to say a) that this was an important factor in cost disease for health care or education, etc. or b) that executive pay has been a major driver of costs in the private sector. It was merely an example to point out that the privates sector is also vulnerable to seemingly irrational rises in costs. The point to take is that despite increases in revenues and stock prices, the private sector does not seem to have been able to increase profit margins on average, suggesting that continually rising costs is not limited to the American public sector.

-That being said, I was not making a definitive claim as to the value of executives. The research that I saw suggested no link between pay increases and business outcomes, but I by no means have done a complete examination of the topic.

> Is half a percent of revenue tiny? What percent of profits is it? What percent of their total wages across all tiers of employees? Why should it be considered as a percentage of revenue, other than that being the largest number you can name to compare it to?

If your claim is that executive pay drives up costs, then yes, revenue is a good number to compare it to. The fact that exec pay/revenue is 0.5% or so implies that you could pay executives nothing, take all the savings and put it into price reduction, and still not reduce prices that much (assuming all your revenue comes from selling things).

@gbdub

It is known that increased wages among lower-paid people have a trickle-up effect on the wages of higher-paid people in the same organization.

Among the managerial and executive ranks, does an increase in CEO pay have a trickle-down effect on the pay of their immediate underlings (trickle-down through the executive, and possibly managerial, ranks)?

So where is most of the money from profits actually going, if executive pay is not a large percentage? I’ve read a number of articles which seem to say that most of the profits are not actually being re-invested in things like expanding production or developing new products, see here and here and here and here.

???

Executive pay doesn’t come out of profits. It’s a cost, just like the pay of everyone else.

I am aware that practice in the financial industry is to sum up the firm’s operating income for the year and then set the bonus pool as a portion of the tentative “profits.” Of course the bonuses paid out of the pool show up as a cost on the annual report and the tax return, when the actual profit/loss for the year is calculated.

(I believe this dates back to when all the Wall Street firms were organized as partnerships and the bonus really was each partner’s distribution of the year’s profits. Once ownership and management were no longer exactly the same people, the terminology wasn’t quite accurate anymore.)

OK, fair point. I shouldn’t have said “profits”, but the basic intuition behind my question was that some expenditures are more forced on a company by the market (capital expenditures like manufacturing equipment, and salaries for lower-level jobs for which there less variation between companies) and some are more a matter of choice (like expenditures needed to expand production or develop new products), and executive pay is more on the latter side of the spectrum. And the latter part of the spectrum is probably what you want to pay more attention to in order to figure out where the money is going when companies are able to get increasing amounts of money from sales (whether due to being able to charge more for their goods/services without a significant decline in customers, or due to a growing number of customers) while the money they pay to employees isn’t increasing proportionally.

So, I’ll just rephrase my question in terms of what corporations are actually doing with the total money they make from sales–if there is plenty left over after you subtract costs such as executive pay, non-executive pay, capital expenditures needed to maintain existing production, and capital expenditures for expanding production, where is that money typically going for all the corporations that don’t pay dividends directly to shareholders? (which is apparently true for the majority of corporations on the stock exchange, only the biggest and most well-established pay dividends)

They put it in the bank, basically. There is a line item for cash. They can make small amounts of interest with near-cash equivalents. From there, investments may be made, or new departments created, or budgets increased, etc.

Your concern with executive pay with respect to profit seems odd because that’s a fight between the shareholders via the board and the C-suite. Generally the shareholders demand growth from the C-suite and are not looking to cut cut costs in that area, which as noted is a tiny slice of the revenue pie.

Increasingly, stock buybacks (minus a recent dip).

http://www.cnbc.com/2016/10/28/why-are-stock-buybacks-lower-in-2016.html

They’re weird. It’s the company intermediating between shareholders. I guess that it’s done for tax purposes, but I’d rather companies be incentivized to give dividends and periodically reverse split. Then individual shareholders could decide to buy or sell on the open market.

With buybacks, shareholders who choose not to sell to the company end up as larger stakeholders (after factoring out dilution through stock options). With dividends and reverse splits they will only end up as larger stakeholders if they actively choose to directly purchase more stock from other shareholders on the market.

Leaving aside the tax consequences, all buybacks do, compared to dividends, is change individual shareholders’ default behavior to effectively buying more shares of the same company, versus wherever they would have reinvested a cash dividend. Those who have a real problem with this can always counteract it by selling a few shares. It’s not unreasonable to wonder whether it makes sense to have a tax code that encourages buybacks– but as a shareholder, as long as the tax code is what it is I’d rather have companies taking advantage of it.

For a corporation that doesn’t pay stock dividends or use money for stock buybacks, does the annual amount they spend on things relevant to production–equipment, employee salaries, etc.–tend to approximately balance out with the annual amount they put in the bank, if you average over a long enough time? The links I posted in my first comment gave me the impression that the typical corporation was making significantly more money than they actually invest back in production, so I wonder if that means that over time a larger and larger proportion of a corporation’s net assets is just money in a bank that’s not doing anything for them aside from growing due to interest. But I suppose it’s possible that large spending comes in bursts so the amount spent vs. the amount put in a bank over the most recent year might look fairly different from a 10-year average.

Also, do you (or anyone else) have any suggestions about sources I might look at to find broad estimates of how the money from sales is allocated percentage-wise (including capital expenditures, employee salaries, money put in the bank, stock dividends, money spent on stock buybacks, and any other major categories) for an average corporation, or for particular categories of corporations?

Okay, promised reply with further reading.

First start by Google scholar searching Executive compensation (and variants like CEO pay.)

The relevant literatures (other than just Google Scholaring executive compensation, which I HIGHLY recommend) are:

1. Theory of the firm.

2. Asymmetric information

3. Principal agent problem.

4. Theory of ideal contracts.

I also recommend:

1. Comparison of similarly sized firms remuneration packages between Europe and the U.S..

2. A general look at studies of institutional capture in the private sector.

3. Stuff on history of the firm in the 20th century, and overhaul s of firm function like the shareholder revolution.

4. In a more sociological vein, Miliband`s work on the power elite.

Related my but not quite on topic, I would suggest any full length treatment of this should include reference to relative income effects.

This popular treatment by Krugman may be a good start http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2001/06/25/305448/index.htm

It seems like it’s a known fact for anyone who thinks running a bigger company justifies a larger salary. After you adjust for changes in the size of firms, is there anything left to explain? Try this:

Okay. One study. For almost any issue X, I can find a study that says, “Y explains X”, and say “Case closed!”

In general, you want to look for survey articles. Here’s a recent handbook chapter:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers2.cfm?abstract_id=2041679

This is still very much an open question. Here’s a paper published this year that offers an explanation, and describes it as a “long-standing puzzle”:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304405X16301477

While I think that paper is a reasonable explanation of the phenomenon, it is very different from your description. It does not say that the size of the firm predicts the salary. It says that the existence of big firms increases the salary at small firms.

Wouldn’t it be nice to believe that I followed just such the right blog that this voting method got me closer to the truth?

That voting method will get most people closer to the truth on most blogs.

Define “most”.

I find this claim highly dubious.

crowdsourcing theory as advanced by the maker of this blog ?

not a counter to your argument, but the beginning of one certainly

If we make enough assumptions about the the distribution of opinions of commenters and followers on blogs and imagine truth as evenly distributed somewhere within the range of opinions, then revising an opinion in accord with this voting method will decrease the expected difference between the opinion and the truth; this for the same reason that boarding the subway in the middle will minimize the expected distance to the exit once you deboard at the destination station: the voting method brings you closer to the middle and the middle is closer to the ends than any end is from another. Problem is, I doubt that the sorts of assumptions needed hold and that truth works that way.

Um, do you experience distance dilation when you walk on subway platforms? Because if the cost of walking is just linear in the distance, the expected cost to get to one end (with 50% chance of it being either end) is the same no matter where along the train you are. This means you should just board at the closest door.

If you want to reduce the maximum distance to the unknown end, then yes, head for the middle of the train (or, technically, whichever part of the train will end up closest to the midpoint between ends at the destination station).

Of course, usually you have some time to kill before boarding a train, and would like to make efficient use of your time. So you get on the train at a point you know will be closest to your actual exit at your actual, known destination station.

(Not that I’ve spent countless idle commuting minutes thinking about this or anything.)

@Machina ex Deus

Where I live, exits can be anywhere along a subway platform. If you deboard a subway at an extreme end of the platform then the expected distance to the exit is 0.5 of the total length of the platform. If you deboard in the middle your expected distance to the exit is 0.25 of the total length of the platform–the exit is a random distance up to 0.5 a platform away from you in one or the other direction. This is a useful method for deciding where to wait for a train when you have time to walk along the platform before it arrives and want to save time (minimize expected time) walking along the platform after you deboard.

So to summarize: 90% of the economists in the known universe responded to your post… and not one of them even attempted to give FACTUAL answers to the questions you raised, questions which are fundamentally about ACCOUNTING, not vague societal forces?

School prices are up 2.5x over 40 years in real terms; that means they’re up like 10x in real terms.

Instead of 10000 words about long tails or whatever, can we get the LITERALLY 5 SENTENCE accounting answer of what drove that increase? Teachers per student is up X%; mean teacher compensation is up Y%; administrative staff per student is up Z%; mean staff compensation is up W%; auxiliary staff (gym, coaches, whatever) is up Q% … etc … real estate spending is up R%, of which S% is due to rising prices and T% is due to more space per student; legal compliance spending is up V%. And then some remarks about new classes of teachers, distribution of compensation, and geographic variability of these changes.

There MUST be a study on that, right?

Does that study not exist? If it doesn’t, how freaking incompetent is the economics profession? If it does, why have none of the 50 million people in this conversation summarized the major results?

I think this is a valuable meta-question. To start off with, we know that the people who responded in the comments and the linked articles are not “90% of the economists”. Most of them, it would be misleading to call them economists at all (or professional economists). But there do exist professional economists, and so three possibilities arise: 1) they have considered and responded to these issues, citing the relevant studies, in (presumably) more academic media; 2) they have failed to consider these issues because, to a professional economist, they are obviously not a Big Deal; 3) they have failed to consider these issues by some failure of insight or some other bad reason. Except in case three, the answer for you (based on my read of your having been unsatisfied with the resulting conversation) is to read more professional-economic sources than this blog, and so hopefully base your resulting views on something more detailed than the mostly unsourced musings of three hundred anonymous internet users.

“If you’re unsatisfied, go away” is not a helpful response from the perspective of the community as a whole, nor is it very polite.

The rest of your comment makes no real point. “It could be A, B, or not A or B.”

I think that it’s a very helpful response. Most of us either do not want to or cannot become master economists, and it’s largely the same few people commenting every time. The solution in the community is to attract more economists, the solution for OP is to read more economic studies and stop yelling at us to become more interdisciplinary. And I will mention that OP wanted qualitative data, but Scott had already given that to us in his original article, and these are comments from a discussion of that data. We don’t have specifics, but what kind of industry is going to release a financial report organized like that, if it’s going to be damning? Who would finance the financial report?

I’ve noticed a general amount of tension that occurs in discussions between specialists and non-specialists. Generally speaking, specialists allude to large bodies of research and implicit understanding within their fields, while non-specialists ask for specific rebuttals and citations, and accuse the specialists of appeals to authority.

I think what’s going on is that there are two sorts of humility — there’s proper epistemic humility (you don’t know what you don’t know), and there’s improper social signaling humility (how dare you, lacking the proper academic credentials, question the priests and scribes?). And both sides are guilty at times of doing this the wrong way.

The fact is that there actually is a huge complex literature on almost any important issue, and there is a large body of implicit and widely understood knowledge among specialists, that is very difficult to communicate to non-specialists in the space of a blog post (let alone a blog comment).

But it is *also* true that there are a lot of BS status games in academia, and fields have blind spots, and sometimes a smart outsider can ask useful questions. And as a general principle, it’s right to not accept appeals to authority and to ask for specific arguments and citations.

But the key is that one should ask for these while showing proper epistemic humility, and that specialists trying to communicate the inferential distances need to be less condescending and more open to considering and responding to criticism by outsiders (and less insistent on being shown proper social deference).

+1

+2

There’s another kind of non-social, yet still interpersonal signalling: “Hey dummy! I’ve spent literally hours studying this topic (or this particular sub-idea within the field) that you obviously know nothing about. Go away and come back when you have a clue!)

Just saw this after I posted my comment. I would add that we need to look very finely at these categories. E.g. there is a big difference between Bertha the receptionist and Thomas who is head of… I dunno “Synergistic and integrative policy solutions” when it comes to admin in health and or education.

I agree in principle (that nuanced accounting is necessary for good understanding), but even the crudest breakdown would be infinitely more informative than the rampant theorycrafting going on.

If we had the answers to his questions, even if the categories are wrong, we can still have a starting point to figure out whose ox is getting fat.

The only oxen getting consistently fatter, however, are governments. The cost disease isn’t resulting in huge profits for any one entity in these areas; the money is mostly getting spread around.

I’m not An Economist, but I pointed to detailed observations regarding the cost increases in health care, the topic I knew something about, on r/slatestarcodex of a nature I assume is not that dissimilar from the one you request. A primary driver of rising health care cost is medical technology. If you want a percentage, I can’t give you that, but there are lots of studies indicating that this variable has been a key variable for some decades. I refer to chapter 14 of the Oxford Handbook of Health Economics, from which I quote in that comment, which has a lot more on these and related topics (as do other chapters in the book, but that one is the main one on these topics).

Incidentally considering how complicated cost accounting and the problems pertaining to how to accurately account for cost in the medical sector is, I would strongly caution against simplistic, if accurately-sounding-, theories on these topics (in particular, but not exclusively). An exchange I had with Tibor a while back here springs to mind, in particular perhaps the notes I made towards the end of that exchange. I don’t think anybody should be expected to have the sort of knowledge you need to properly assess/evaluate cost developments in all the areas Scott talked about in his original post. I don’t have time to look at the links Scott provided, but assuming any of them is any good my advice would be look for expert opinion on particular topics (real estate, schooling, health care, etc.) and then proceed from there. If the person in question seems to proceed from an assumption that said individual is/can be an expert on all of them, he or she in my humble opinion most likely doesn’t have a clue how complicated the subject matters about which said individual talks really are (here I may, for all I know, be insulting some Big Name Economists to which Scott links in this post – as mentioned, I haven’t followed those links – but that doesn’t really change my view on the matter. Even an implicit assumption to the effect that a health economist can be An Expert on both institutional aspects of health care organization, the contribution from the regulatory structure and how this may vary across countries, cost accounting methodology, cancer cost development (…which cancer?), diabetes cost development (I know from my look at this research that diabetes is different from e.g. infectious disease, and so what works to cut cost (/or explain cost) in a diabetes context may not be what works to cut (/explain) cost (developments) in an infectious disease context), end-of-life health care cost developments over time, long-term care cost developments and how this varies with e.g. the prevalence of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s… is not reasonable, in my opinion).

Of course, you have to be careful with this sort of summarization because it can be true in different ways. An EpiPen is medical technology, and could serve as an instance of more money going into medical technology. But that doesn’t in an of itself explain why a basically unchanged product costs so much more now than it did. If suppliers of medical technology have more price control than suppliers of medical services, you would want to look further for reasons for that.

All I’m saying is that we shouldn’t look at the broad sectors and conclude “Oh, there’s more technology so that explains more spending.”

You also shouldn’t take a single product and point at it and say that because this product costs more now than it did in the past in real terms, that means …well, anything really. The pricing model of a specific medical product or service is highly unlikely to be at all informative about the contents of some sort of semi-sensible Model of The General Development of Medical Costs over Time.

“If suppliers of medical technology have more price control than suppliers of medical services, you would want to look further for reasons for that.”

Even a simple statement like this one, in combination with what came before it, contains/reveals multiple questionable implicit assumptions, which is something that often happens in these contexts as also illustrated by my exchange with Tibor. I’ll point out two.

a) A high price of a good/service does not imply that said good/service contribute significantly/positively to health care cost growth, or have done so in the past. A high unit price may in fact do the opposite, by virtue of a high price limiting adoption/utilization. It’s very common in the medical sector to see improvements in productivity as a result of a technological advance leading to lower unit prices combined with higher total outlays as a result of increased utilization – this phenomenon increases cost growth over time, not the opposite. Technologically driven health care cost growth doesn’t just derive from expensive cancer treatments and stuff like that, it also derives from various goods and services that have become cheaper over time and therefore accessible to a large number of people who did not in the past have the option of receiving the good or service in question. A high unit price leading to limitations in utilization can on the other hand be a factor limiting cost growth.*

…Of course in the context of this discussion you can then proceed to quibble about/have a discussion about whether there might be some cost associated with not treating people who might have been treated if the unit cost was lower, and if you do that you start entering the huge world of cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit studies, which may have addressed that question in the specific context you’re interested in.

b) The implicit costs = spending (/outlays) assumption in your comment is deeply problematic and I was thinking about going into that in my first comment. Outlays are usually what people worry about, but there’s a lot more to medical costs than just outlays, at least if you want to do any sort of thorough cost accounting. In the context of some of the diseases contributing significantly to medical outlays, a very substantial proportion of the total cost are non-monetary cost. I refer to my exchange with Tibor.

Yeah, I know it’s complicated. So do the people who contributed to the literature to which I allude. They figure technology is a big part of the story. They in my opinion, to the extent that I have one and am familiar with the research, have good reasons for claiming this. There are lots of other things of relevance if one is worried about medical care affordability long-term, and lots of things that are relevant because they affect cost levels (rather than cost growth rates) to a significant extent, but if you want any sort of big-picture explanation in the medical context then it really makes a lot of sense to include technology as a major component.

…

*I’m currently reading a text addressing among other questions the extent to which disease incidences are correlated over time; if you get cancer, are you more or less likely to get diabetes as well? Stuff like this. This kind of stuff is highly relevant for cost growth estimates and trajectories. People who don’t get a disease usually get another (/have a higher likelihood of getting a different disease), and that another one might be more expensive to treat. This sort of thing means that even if you were to completely remove a disease from the equation, with all the costs associated – let’s say you cured disease X tomorrow, and nobody ever gets it again – you could easily end up with an outcome where medical costs are actually now growing faster than they did before. To get a proper perspective of cost growth you need to evaluate the alternatives, and that’s sometimes quite difficult to do.

Let’s go back over what I said.

So a particular finding could be explained in different ways.

Here is one scenario which is consistent with the particular finding but if things were a certain way would not make that first finding explanatory. So: an explication of the first point, which also makes no specific claim other than a particular unchanged technology has changed in price. That is: I make an empirical claim that epi-pens are largely unchanged but have gone up in price.

This is a conditional, and therefore does not claim that suppliers of medical technology have more price control than suppliers of medical services. It is a claim that if they did, that could be explained by multiple reasons. This is therefore a very, very bland statement. It carries none of the implications you discuss, and then go on to be a condescending tool about. Condescending and oblivious: pick one.

Here I sum up the point I was making. Note that the “All I’m saying” phrasing emphasizes the not-making-other-claims thrust of the contribution.

“I make an empirical claim that epi-pens are largely unchanged but have gone up in price.”

And I make the claim that this is completely irrelevant to the discussion at hand, which is about medical care cost growth in general. The price development of one good or service will tell you nothing relevant. Whether service providers have more or less market power than e.g. pharma companies is a different question, but again one that doesn’t really get us anywhere if the interest is in health care cost growth; a high level of market centralization is not why health care costs are growing as fast as they are (although “Clearly more work on the causal pathways underlying the relationship between costs and competition is needed” – Oxford Handbook … p.319).

In the specific context of this debate it made sense – to me – to assume you were trying in your comment to make claims or points which somehow related to the topic of discussion at hand, which is medical care cost growth. I don’t see how I could have known that you did not, and assuming the person with whom you are debating is trying to be on-topic seems a decent default position to me.

Shorter and slightly-more-to-the-point me: I think you were easier to misread than you imagined you would be. Someone who has spent time familiarizing him/herself with what this literature has to say about various things will in my opinion likely read your comment in a different way from the way you read it or would prefer it be read.

And as a final note, if all you were aiming to do was to get to that final observation of yours, you might be interested to know that that is not what the researchers who have worked on this stuff have done.

Epi-Pens are a great example, several competitors were hit by recalls or delayed FDA approval, and suddenly Epi-Pen found itself approaching a government granted Monopoly.

We don’t know why this happened although Epipen’s manufacturer was a very active lobbyist and Obama administration Donor. Which actually is a flaw in the essay, it assumes that Market participants have all kinds of motivations, but that government is motivated to do good. This might be a constraint in large obvious things like banning murder, but how many people vote based on the day to day actions of the FDA?

If it’s not many then a whole different set of corrupt incentives come into play. In that case I’d rather have a market, greed is at least honest (well greed is omnipresent, in a market I know how it’s being satisfied)

Tibor? Isn’t he the guy that’s always messing things up?

That’s Loki.

Aren’t you jumping the gun? I counted four well-known economists and as far as I know, none of them are specialists in these areas. There probably is literature on it but you just don’t know about it.